| Note: Although America’s Impressionism: Echos of a Revolution was scheduled to be presented at the Brandywine Museum of Art from October 9, 2021, to January 9, 2022, the exhibition was not able to be shown due to the Museum being closed unexpectedly. |

One of the most enduring—yet complex and even contradictory—styles of art ever produced in this country, American Impressionism captured and held public attention for more than a century.

The style was appreciated for its fairy tale views of an elegant American yesteryear, while at the same time carrying the imprimatur of Paris and reflecting the origins of modernism. Throughout the twentieth century, the American practitioners of the French-born style found themselves in both the good and bad graces of critics and the academy─praised for boldly adapting a new style and at the same time impugned for the style’s perceived indebtedness to foreign masters. Art critic Christian Brinton cautioned in 1916: “It must not be assumed that American Impressionism and French Impressionism are identical. The American painter accepted the spirit, not the letter of the new doctrine.” One hundred years later, Brinton’s words still ring true. Digging deeper into their origins, the exceptional works of American Impressionism assembled in this exhibition revealed a nuanced history of art interchange in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, far more complicated than the straightforward imitation of a foreign style.

The exhibition endeavored to explore more fully a redefinition of American Impressionism as a practice less intent on mimicking the French style than on creating an equally independent movement in this country. Of key concern is the belated arrival of Impressionism in America—largely introduced in a major New York exhibition spearheaded by the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in 1886. Whereas French Impressionism burst onto the Paris scene with a shocking exhibition in 1874, in the United States, the style arrived after more than a decade of discussion and debate here and abroad. At first abused in the French and American press, Impressionism found champions on both sides of the Atlantic. The interim years, up to and including the 1886 exhibition, provided a critical distance for American artists, critics, collectors, and the general public to determine what Impressionism’s impact would be on American shores.

Giverny and Beyond

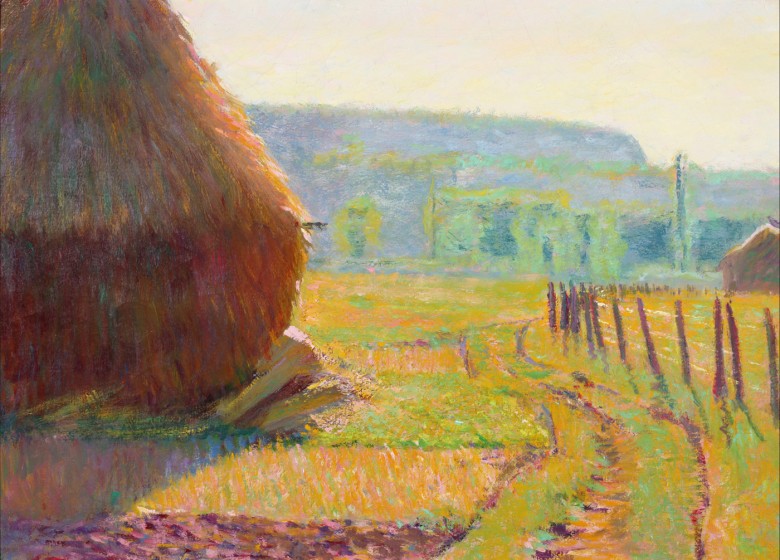

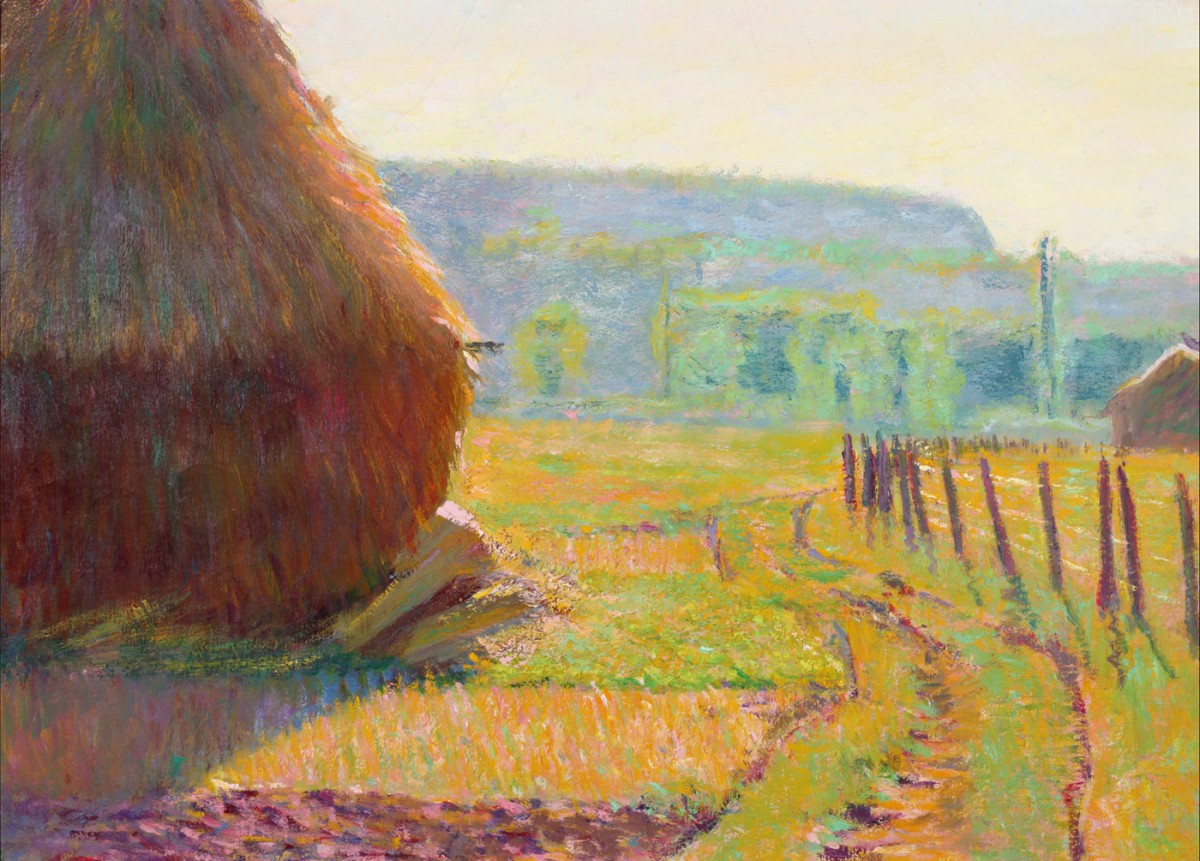

The archetypal French Impressionist Claude Monet modeled a form of Impressionism—concentrating on the suburban and rural landscapes—that held perhaps the greatest appeal for American artists in France and collectors in the United States. The exhibition will present his vast influence through the work of American artists who gathered around him in the countryside of France. Never one to linger in Paris, Monet rented a home in the village of Giverny in 1883—which he was able to purchase in 1890 due, in part, to his success in the American market—where he remained in residence until his death in 1926. The same success that allowed Monet to live more or less in seclusion in Giverny also drew American artists to him, though he held no formal or informal classes. By 1887, a group of “Givernyites” including Willard Metcalf and Theodore Wendel had gathered in the village to carry on plein air painting in the manner of the French master. Like many Americans to follow, these two focused on the landscape, creating paintings that echoed Monet’s choices and compositions.

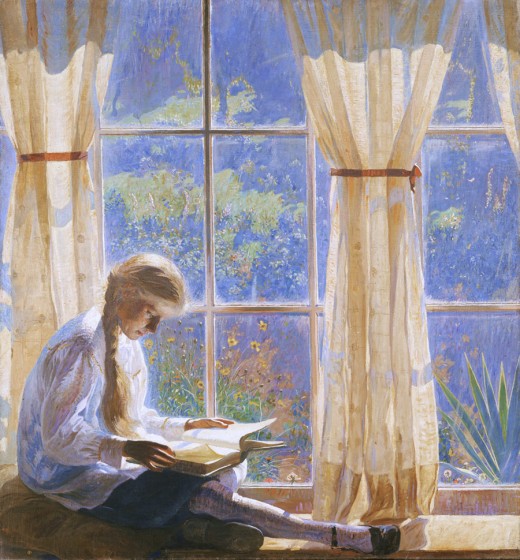

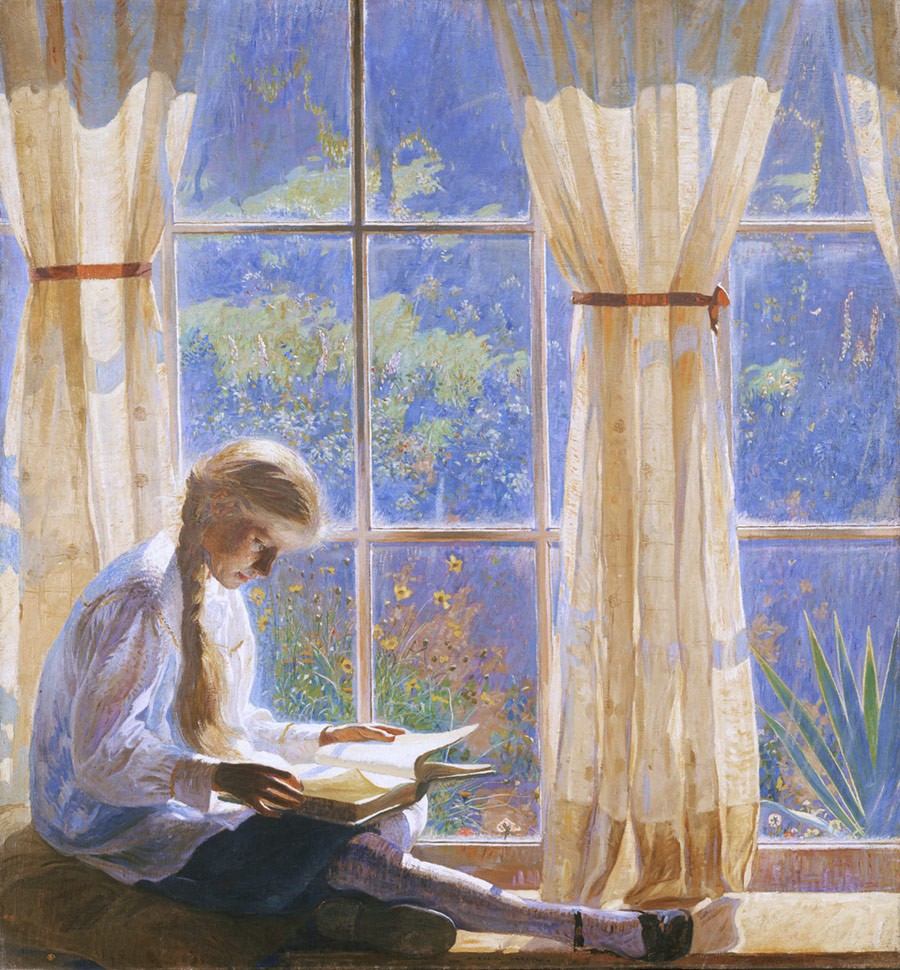

Assessing how Monet’s Impressionism varied from that of other practitioners aids in understanding the Americans’ preferences for pastoral scenes, free of direct reference to the city, social ills, political statements, or evidence—other than the painting technique itself—of the modernizing world. Figures appeared in Monet’s work at Giverny primarily as a complement to the landscape, a trait transferred to Americans such as Robinson, who presented humans as a part of a world of idyllic leisure, disconnected from urban life. In this way, Monet’s American followers were creating works already in ideological harmony with the American colonial revival.

Across the Continent

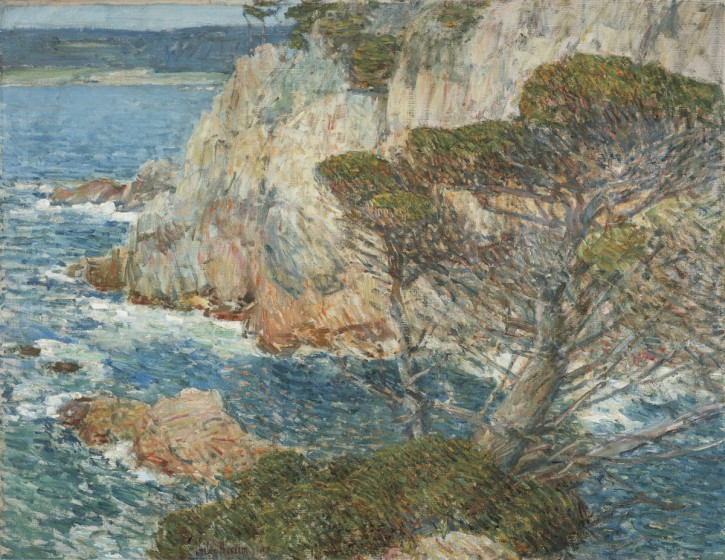

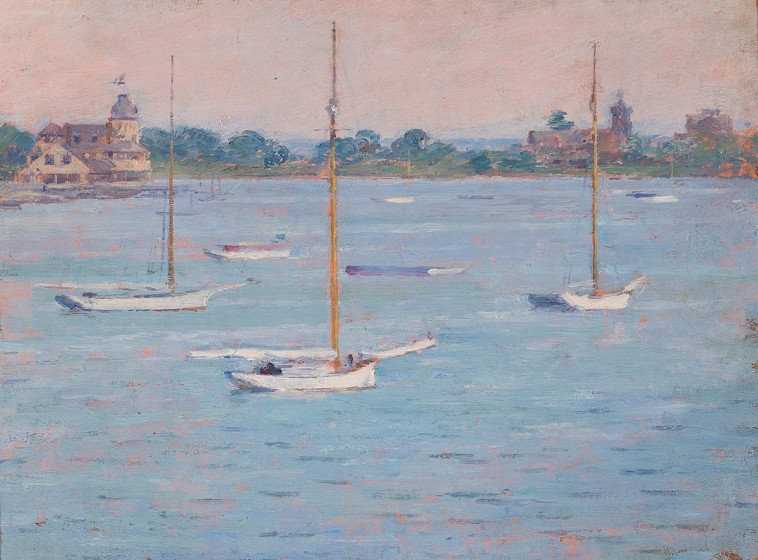

Impressionism’s American transformation did not end with its transatlantic voyage. The colony at Giverny, among other European spots, inspired an Impressionist pedagogy in this country, where colonies first sprang up at locations easily accessible from the New York art world. The style eventually reverberated across the country with regional distinctions. For many, American Impressionism finds its ultimate expression in Northeastern locales, such as Old Lyme, in Connecticut, and Shinnecock on Long Island. In these and many other colonies, the rural villages of France were recreated within America’s borders, often producing work with a markedly nationalistic undercurrent, emphasizing the style’s geographic relocation. Examples in the exhibition by such artists as Childe Hassam, William Merritt Chase, and Willard Metcalf, with their lush garden or seaside imagery, form the backbone of American Impressionism in the twentieth century.

As variations on American Impressionism developed, reputations for regionally specific subject matter grew in conjunction with the American extensions of Impressionist techniques. Individual artists became linked with these regional expressions. Some artists moved between these regions to capture the seasonal beauty or signature landscapes of different locales. Impressionist art colonies continued to develop and thrive well into the twentieth century, moving into the American Southwest and to the coast of California, areas sometimes left out of broader histories. The exhibition will round out the transformational history of American Impressionism with examples from these further afield regional impressionist landscape painters including Guy Rose and Julian Onderdonk.

A Persistence of Moments

In addition to Impressionism’s broad geographic reach in the United States, the temporal scope of the style is of significant interest in this reevaluation. Landmark exhibitions such as the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the 1913 Armory show in New York, and the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco featured American Impressionism alongside even more radical developments in modernism. The style’s persistent popularity, maintained by a steady stream of practitioners and a healthy patronage, provided a foundation to American modernism in the early twentieth century. The style proved a springboard for many more avant-garde ventures in American art, which rose and fell quickly over the decades. It is poignantly ironic that an artistic movement based, in large part, on the enterprise of capturing momentary visual events in paint should linger so long on American palettes.

The exhibition presented the story of American artists coming to terms with a new modern style through approximately 50 important works drawn from public and private collections across the country. A number of works represent the enclave of Americans working in Giverny, tracing the formation and transplantation of the style back to these shores. A fully developed American Impressionism, which persisted for decades after the introduction in this country, shows itself as reliant upon subjects very selectively drawn from the French predecessor, creating an Americanized version of what is truly an international style. Finally, examples from the regional variations of American Impressionism demonstrate the creative avenues opened by this experiment, which were fundamental to twentieth-century American art. In re-examining the transfer of a European style to the United States, the selected works offer a window into the complex act of translation as Impressionism was introduced, imitated, and modified over a period of fifty years.

Publication

The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue published in conjunction with Yale University Press and including a full complement of color plates. A featured essay by the exhibition’s curator, Amanda C. Burdan, examines the pre-conditions for American Impressionism, broadening the style from its accepted French foundations. Early European experiences shared by such American Impressionists as William Merritt Chase and John Henry Twachtman—including their studies in Munich and Venice—colored later interactions with French Impressionism, suggesting a wider international underpinning for American Impressionism. The emergence of American schools of plein-air painting, as practiced by Winslow Homer, and Tonalism in the vein of George Inness, also appears to be a common “pre-condition” for American Impressionism.

Additional scholarly essays were contributed by Emily Burns, Assistant Professor at Auburn University and author of the Transnational Frontiers: The Visual Culture of the American West in the French Imagination, 1867-1914; Ross King best-selling author of several critically-acclaimed histories including his most recent book, Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies; William Keyse Rudolph, the Marie and Hugh Halff Curator of American Art and Mellon Chief Curator of the San Antonio Museum of Art and curator of 2009 the exhibition Bluebonnets and Beyond: Julian Onderdonk, American Impressionist; Kevin Sharp, the Linda W. and S. Herbert Rhea Director of the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, and author of many works on American Impressionism including the essay “How Mary Cassatt Became an American Artist” in the catalogue of the exhibition Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman; and Scott Shields, associate director and chief curator at the Crocker Art Museum.

This exhibition was co-organized with the San Antonio Museum of Art (on view June 11–September 5, 2021) and Dixon Gallery and Gardens (on view January 23–April 9, 2021).

America’s Impressionism: Echoes of a Revolution presentation at the Brandywine is supported locally by The Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts, Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation, and Robert Lehman Foundation as well as donors to the Brandywine River Museum of Art Exhibition Fund, including the Wyeth Foundation for American Art, Davenport Family Foundation, Ms. Mary Graham, Mr. and Mrs. Anson McC. Beard Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Michael R. Matz, Dr. and Mrs. John Fawcett, and Morris & Boo Stroud.