In the Footsteps of the Artist

Visitors to the N. C. Wyeth or Andrew Wyeth studios know just what a powerful experience it can be to stand in the place where a work of art was created. This applies not just to the artists’ studios, but to other places in the world where an artist set up an easel and captured the view. There are so many comparisons to be made between the “real” and “painted” view and for a moment you can glimpse the artist’s intentions and choices.

At Kuerner Farm, visitors can readily see the correlation between the window and yellow wallpaper of Anna’s kitchen and the scene presented by Andrew Wyeth in Groundhog Day. Visiting the Brandywine Battlefield, you can immediately identify the sycamore tree that appears as the centerpiece of Andrew Wyeth’s Pennsylvania Landscape.

Perhaps because Andrew Wyeth is so often considered a realist painter, it comes as a surprise to see that the paintings and the facts of the physical world don’t always match up completely. Wyeth was particularly skilled at editing his scenes, removing or moving elements to suit his compositional needs.

The artist Childe Hassam (1859-1935) is usually classified as an American Impressionist, so perhaps one expects less verisimilitude in his paintings owing to the avant-garde nature of his style and the creativity of his brushwork.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit Appledore Island, the southernmost island in Maine, and part of the Isles of Shoals, where Hassam painted over the course of many summers. Along with scholars and curators from across the country, I realized how absolutely faithful Hassam was in his representations, so much so, that more than a hundred years later, you can still identify the exact location of nearly all of his paintings from the island.

Hassam had a few tricks up his sleeve, of course, that still make for some surprising findings on the island. Occasionally he would make “mountains out of mole hills” so to speak, by framing a view such that the rock formations seemed absolutely monumental, when really, they were quite human scale.

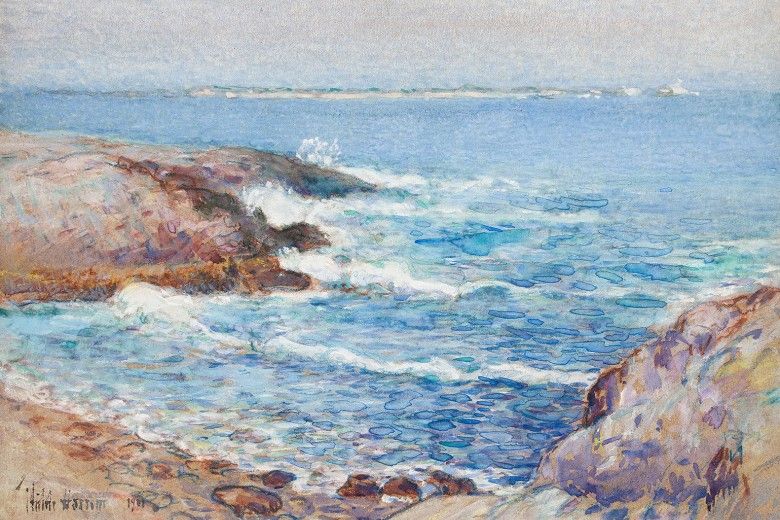

Given the opportunity, I couldn’t resist trying to find the exact location from which Hassam painted the Brandywine’s watercolor Broad Cove in 1901. Although the tide wasn’t quite at the right height to make an exact match, standing on the south side of the cove, looking to the northeast, from a hillside vantage point, I think I found the spot.

And it wasn’t just me. Curators from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Florence Griswold Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the North Carolina Museum of Art and others all found the precise places where paintings from their collections were made as well. With the assistance of Hal Weeks, marine ecologist and former Assistant Director at the Shoals Marine Laboratory, very few Hassam paintings of Appledore have escaped identification.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why Hassam bristled at being called an Impressionist. Despite his broken brushwork and sunny palette, he thought of himself as a realist, painting the world precisely as he saw it. After visiting Appledore, I’d have to agree. He wasn’t giving his impression of the island, he was painting the reality of it.

Image credit: Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Broad Cove, 1901, watercolor on paper, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4”. Brandywine River Museum of Art, Gift of Amanda K. Berls, 1980.