“And life is still thrilling and lovely”: The Story of Katharine Pyle [Part One]

A Passion for Pyle: The Paul Preston Davis Collection, a new digital exhibition from the Brandywine's Annenberg Research Center, is an excellent resource for Howard Pyle enthusiasts and researchers alike! Derived from an extensive collection of archival research materials related to artist Howard Pyle, the Davis Collection was created and donated by local collector and historian Paul Preston Davis. The following blog post, the first in a two-part series written by former Research Center Archivist, Eileen Fay, shines a light on Pyle’s sister, Katharine Pyle—an accomplished author and illustrator in her own right. The Annenberg Research Center contains many books and other publications, including Katharine’s illustrations, from both the Davis Collection and the Diane P. Packer Illustrated Book Collection. Both collections are highlighted in this blog.

One of the many branches of research that Paul Preston Davis followed within his Howard Pyle collection relates to Pyle’s sister, Katharine. Though a well-known author and illustrator, materials related to Katharine can be difficult to find (with the exception of some of her books).

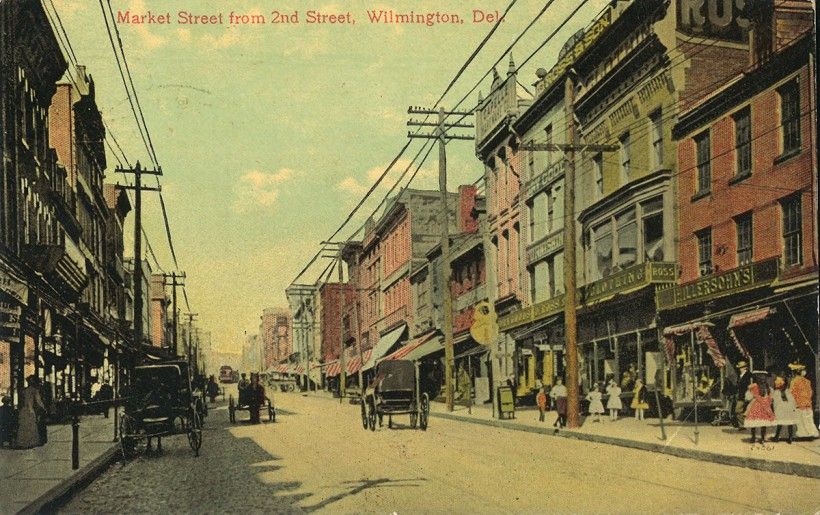

Katharine Pyle was born on November 22, 1863, in Wilmington, Delaware to Margaret Churchman Painter Pyle (1828-1885) and William Pyle (1820-1892). She was the youngest of four living children: Howard, Clifford, and Walter. A fifth, Phoebe, died shortly before her third birthday in 1857. William Pyle was in the leather business, but the economic upheaval of the Civil War reduced the family’s circumstances. By the time Katharine arrived, they had left their comfortable country estate (today the Goodstay Center of the University of Delaware) for a smaller dwelling at 621 Market Street near downtown.

The Pyle children were raised in a creative home. Margaret and William Pyle were members of the Friends Lyceum literary society, and their children were avid readers of St. Nicholas magazine, to which Margaret, Howard, and Katharine all later became contributors. Margaret was also a French translator who was active in local amateur theater. In her unpublished 1937 memoir, Katharine paints a vivid portrait of her mother at work at the round dining room table, which she buried in sheets of paper lined with “her fine delicate writing.” Katharine herself apparently composed her first story at age four or five. She reminisces, "It was about a white mouse that was very proud because it was so pretty and so white, and it wouldn’t play with the other ‘mouses’ or anything, so afterwhile […] the other ‘mouses’ went away and left it alone, and they all got married but nobody would marry the white mouse because she was so proud and she ran away into the fields and ‘cwied and cwied.’"

With the encouragement of Margaret and Howard, Katharine expanded her talents. Many sources claim her first published poem was “The Piping Shepherd” in an 1879 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, but her first poem to appear in print was actually “The Story of a Sad Little Boy Who Cried” (read it online here) in the Letter-Box section of the November 1880 issue of the St. Nicholas children’s magazine. By 1883 her verses were being published in periodicals such as Harper’s Bazaar, Harper’s Young People, The American, and St. Nicholas.

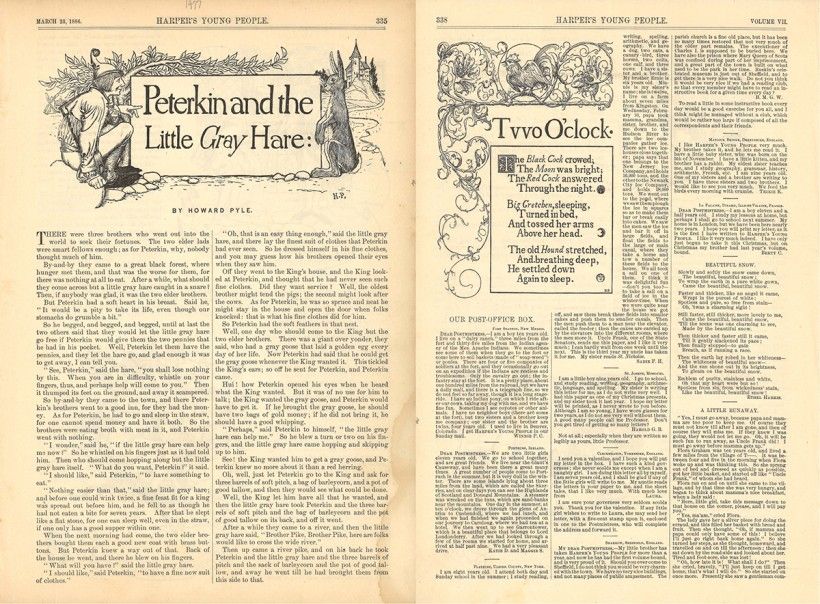

As a child, Katharine attended the Women’s Industrial School, followed by the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. Howard also maintained a strong interest in his sister’s artistic development and career. In 1885 the siblings began collaboration on a series for Harper’s Young People (March 1886 to October 1887) that was later published as the 1887 book The Wonder Clock; or, Four and Twenty Marvelous Tales, Being One for Each Hour of the Day. Howard wrote and illustrated the stories, while Katharine provided little poems and decorative flourishes. During this time Katharine also provided artwork and lyrics for a series of lullabies composed by her sister-in-law Mary Gertrude Pyle née Watson (wife of Clifford). “Song of Autumn,” “Piff-Paff-Puff,” and “Lullaby” appeared in Harper’s Magazine from 1888 to 1889.

Despite this success, her twenties were a period of difficulty and upheaval. As the only woman in the family, the responsibility of running the Pyle household fell entirely on Katharine after Margaret’s passing in 1885. Katharine, in her memoir, describes recurring “attacks of terror” and being plagued by “a miserable strain of morbidness.” The loss of her mother impacted her deeply. Tellingly, Katharine also recalls “the apparent superiority of men over women” as one of her “persistent worries.” Domestic burdens hindered Katharine’s opportunities outside the home.

Another blow came in 1889. Howard and his wife Anne traveled to Jamaica for an article Howard was working on, leaving their seven-year-old son Sellers in his aunt’s care. “I dearly loved him yet I half feared the responsibility, but Howard said he would not be satisfied to leave him with anyone but me,” Katharine wrote in her memoir. “I asked so many questions about him and what I should do if so and so happened that [Anne] grew quite cross. One of the last things I said when they were leaving was, ‘Annie, I want you to remember one thing: if Sellers gets sick, I have done my best for him.’” That may have been an omen, Katharine mused. Though the doctor was not initially concerned, “in less than twenty-four hours after that, Sellers’ bright, gentle, little spirit was gone from the earth.” Howard and Anne did not blame Katharine, yet she never fully forgave herself. Sellers’s memory inspired her poem “The Lost Child.” The first three stanzas are as follows:

Last night I dreamed he came to me.

I held him in my arms and said,

“My little boy where have you been?”

I was afraid that you were dead.”

Then I awoke. It seemed to me

As though my arms could feel him yet.

I had been sobbing in my sleep

My tears had made my pillow wet.

I cannot think of him at all

As the bright angel he must be

Not only as my little boy

Who may be needing me.

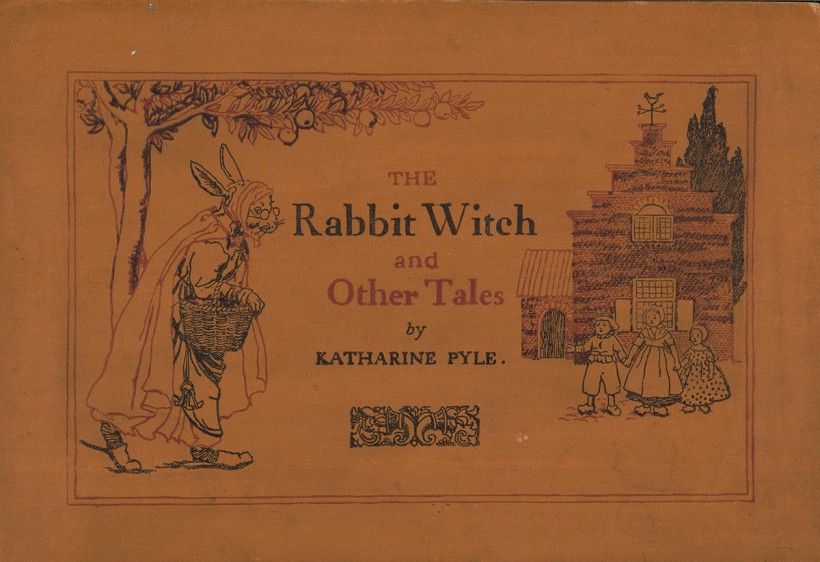

With the death of her father three years later, Katharine finally decided to move to New York City, where she launched herself into the era’s flourishing illustration industry, known today as the Golden Age of Illustration. She networked with Howard’s publishing contacts and took courses at the Art Students League. Her career picked up, as well: in addition to her regular work as an illustrator for Harper’s Bazaar and St. Nicholas, Katharine illustrated the books When Molly Was Six by Eliza Orne White (1894) and In Sunshine Land by Edith M. Thomas (1895). The following year her short story “Out from Fairyland” was featured in the anthology The Children’s Wonder Book: Tales of Mystery, Marvel, and Merriment by Popular Story-Tellers (read it online here), and she made her solo debut with a compilation of children’s poetry she had written for various magazines. Originally entitled Rabbit Witch and Other Tales, it was changed to Careless Jane and Other Tales after publisher E.P. Dutton suggested poor sales were due to the word “witch.”

Katharine admitted she was too easily distracted from her work and returned to Wilmington in 1896, where she began working in a studio adjacent to her brother’s on Franklin Street. It was here that she wrote and illustrated her next book, The Counterpane Fairy, about a sick boy visited by a pixie who tells him a story for each patch in his quilt. Unfortunately, Katharine had failed to heed Howard’s advice on negotiating for royalties and missed out on a significant amount of money after E.P. Dutton advertised the book as “the success of the season.”

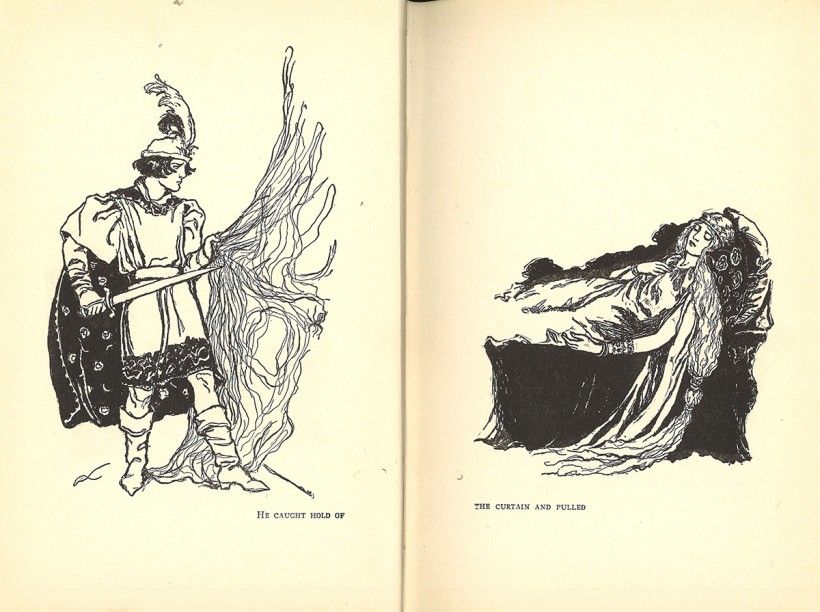

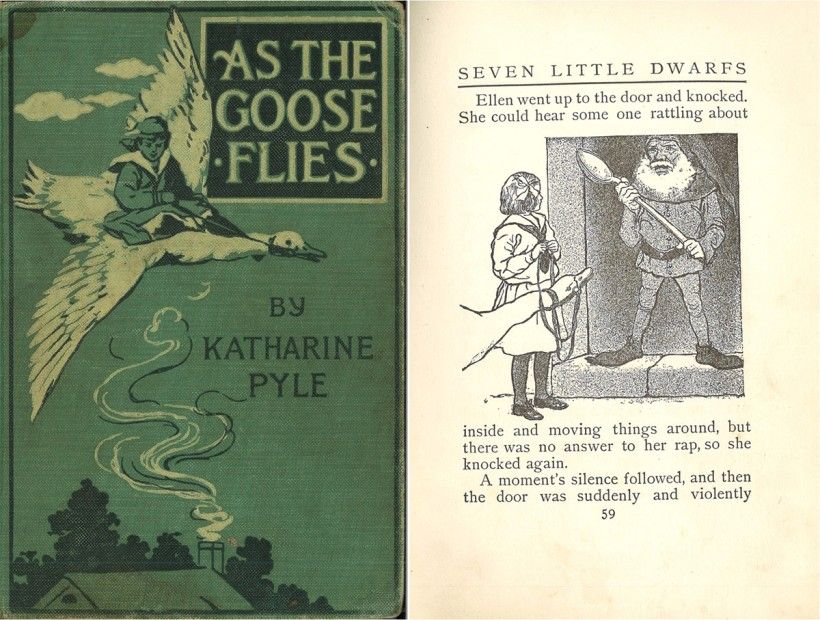

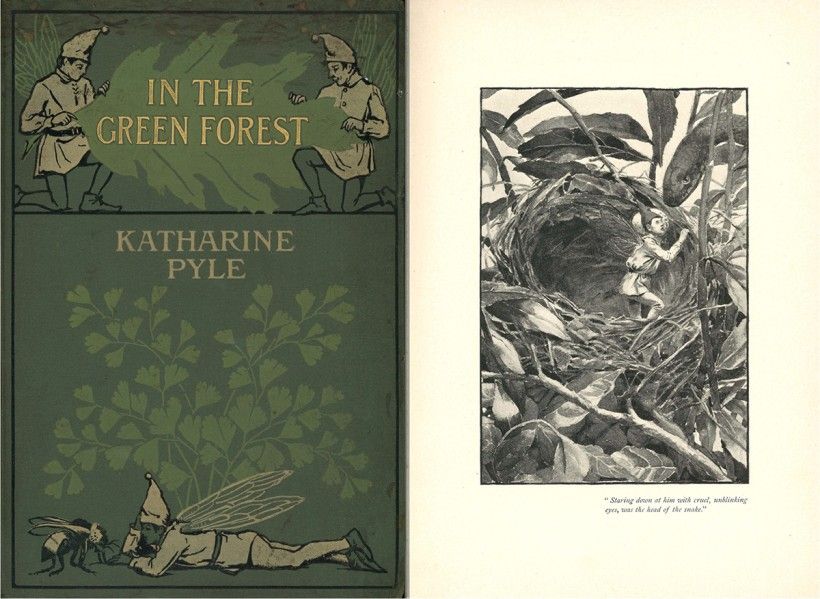

Meanwhile, Katharine continued to illustrate for Harper’s Young People and St. Nicholas. She also illustrated the books ‘Twixt You and Me by Grace Le Baron (1898) and The Island Impossible by Harriet Morgan (1899). Katharine released seven books of her own: Prose and Verse for Children (1899), As the Goose Flies (1901), Christmas Angel (1902), In the Green Forest (1902), Where the Wind Blows: Being Ten Fairy-Tales from Ten Nations Re-Told (1902), Stories of Humble Friends (1902), and Childhood (1904). The last was illustrated by Howard Pyle student Sarah S. Stilwell Weber.

Reminiscing on these works, she confesses, “I think ‘As the Goose Flies’ was a rather stupid book, but it still seemed to sell comparatively well. But ‘In the Green Forest,’ which is still to me one of the best of my books, was never a success. I think it was probably because all the characters in it were fairies, and I do not think children care for fairies as much as for real people. At least I had some very good reviews of it, which was some comfort.”

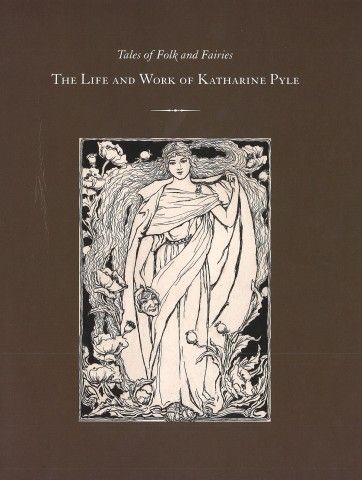

Katharine briefly attended her brother’s illustration classes at Drexel University, where she became acquainted with fellow Pyle student Angel De Cora, who confided in her some of the difficulties she experienced as a Native American in predominantly white settings. Quoting De Cora, she says, “‘People come to the [YWCA] now, and if I’m not in they ask to see my room because it’s an Indian’s. I hate it.’” Katharine was not close with the other women in Howard’s classes. However, several of them, such as the “Red Rose Girls” Elizabeth Shippen Green, Violet Oakley, and Jesse Willcox Smith, formed lifelong friendships. “I lost sight of most of them except for Anna Wheelen Betts with whom I kept up a desiltory [sic] friendship, and Ellen Bernard Thompson, who entered my life in a very vital and intimate way,” Katharine said. Thompson had also provided illustrations for Grace Le Baron’s ‘Twixt You and Me and later married Katharine and Howard’s brother Walter Pyle (his first wife, Anna Mae Jackson Pyle, died in 1903). Katherine L. Miner, curator of the 2012 Tales of Folk and Fairies exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum, characterizes Katharine as “rather a loner, having learned her craft more independently than many of the other illustrators taught by Howard.” She was certainly more established as a professional illustrator than some of her peers and subsequently left Drexel due to the volume of work she was receiving. In addition to writing and illustrating, she created lyrics and artwork for W.W. Gilchrist’s 1896 operetta “Grandmother of the Wind” and composed short jingles for such brand names as Ivory Soap, Shredded Wheat, and Jell-O.

1905 marked the release of two more children’s novels illustrated by Katharine: An Only Child by Elize Orne White and Amy in Acadia: A Story for Girls, fifth in the “Brenda” series by Helen Leah Reed. Other “Brenda” books were illustrated by Howard Pyle students Jessie Willcox Smith, Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle, and their contemporary Alice Barber Stephens.

Katharine’s own juvenile novel Nancy Rutledge came out in 1906, followed by Theodora in 1907. The latter was a collaboration with Laura Spencer Proctor, a journalist who contributed to The Atlantic Monthly. She stayed with the Pyle family for the duration of the project, which "proved one of the most successful of any book with which I have had anything to do,” said Katharine in her memoir. “It almost wrecked our friendship however. I remember a terrible time of coldness—almost of rancor between us over whether a certain sentence should read ‘You would better,’ or ‘You had better.’ Laura inclined to the former; I, to the latter. I really don’t know how we settled it but I know we did settle it and our friendship went on as steadily and strongly as ever.”

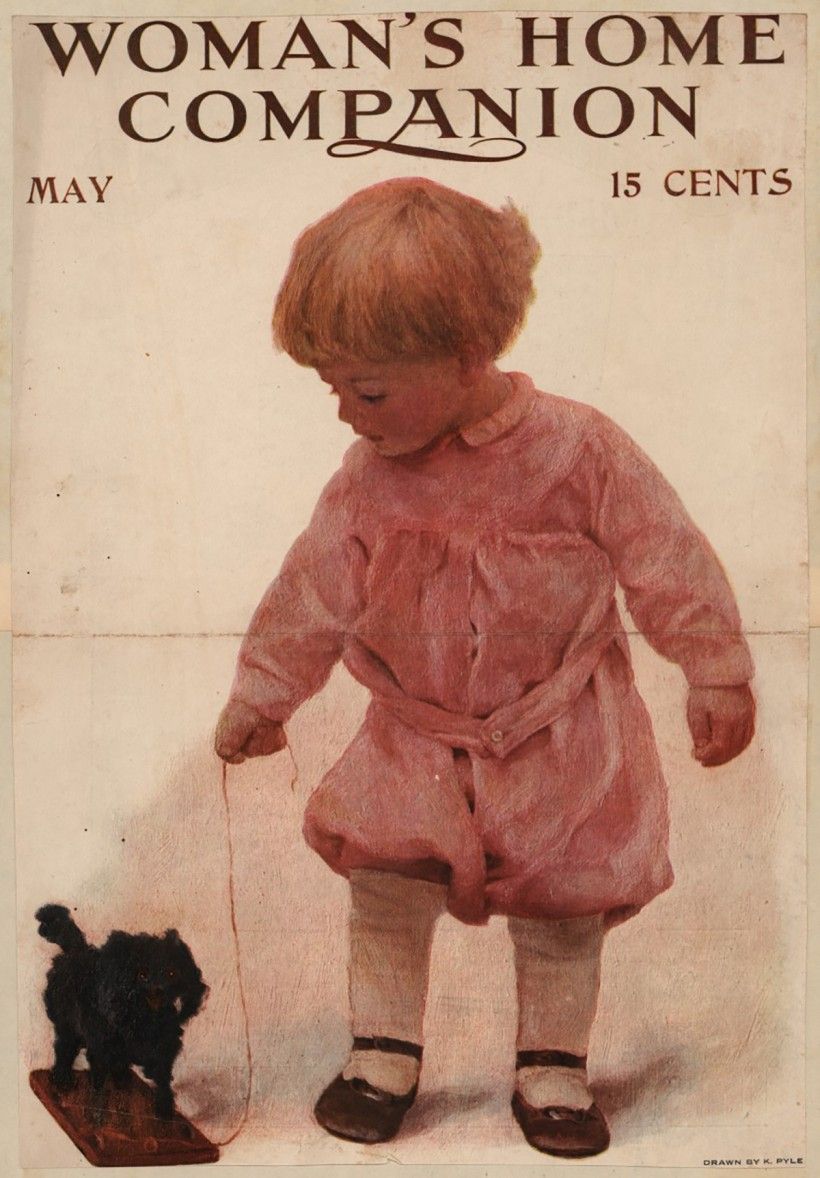

Katharine left for Boston shortly afterward. “After Walter was married there seemed no place particular for me to live,” she recalled. “I never had liked Wilmington; I certainly would not like to live there now that things were so changed. Walter, Nellie and Gerald made a little family themselves and there was no place for me in it, but I did not care to go back to New York. The changes there had been too great.” In Boston she became known for her portraits of local children, most of which were done in nearby Cotuit, where her clients summered. “The mothers and fathers seemed very much pleased with my work but one thing that delighted me more than all the rest was what was said by one of the managers of the Art Museum […] He said, ‘What I like about Miss Pyle’s work is that she gets not only the likeness but the very spirit of the child.’” Another child portrait was Katharine’s cover for the May 1909 issue of Woman’s Home Companion, entitled “The Pink Boy." Her nephew, Walter Pyle, Jr., served as the model.

The constant movement of her friends between Boston and their summer homes meant Katharine was often lonely. She further felt isolated as a wage earner surrounded by wealth. When Walter came to visit one day, she explained, “I poured out the tale of all my loneliness and how I felt I never really belonged to Boston and never would […] He urged me earnestly to give it all up and come home again. He said he would buy for me a house or build me a little bungalow or do whatever I chose if only I would come home.” Following her brother’s wishes, Katharine moved home.

Click here to read Part Two of this series!

Lead image: Katharine Pyle, 1892, Katharine Pyle Files, Delaware Art Museum.