Wind pollination: Social distancing in the plant world

“Keep your distance,” says tree to bee. “I have an invisible friend.”

Pollinators and their partners come in all colors, shapes and sizes. Innumerable assortments of butterflies, bees, moths, flies, beetles, birds and bats are drawn to visit myriad varieties of fragrant, colorful flowers where they sip nectar and collect pollen. Pollination both feeds the pollinators and enables plants to reproduce.

But there is one very important pollinator that is colorless, has no sense of smell and doesn’t drink sweet nectar. Wind pollinates a wide range of trees, grasses and wildflowers. Wind-pollinated plants evolved to keep their distance from pollinating insects and other fauna—yet these plants still depend on pollen to fertilize their flowers and so create the seeds of future generations. It’s estimated that around 10-20% percent of plants worldwide are wind-pollinated (including some that also entertain insects.)

Pollination works the same whether accomplished by wind or animal. A flower’s male reproductive organ (stamen) produces pollen, which is transferred to the female organ (pistil) of that or (usually) another flower, fertilizing it. Typical insect-pollinated flowers have large grains of pollen that stick to its body and get brushed off onto pistils when the insect exits the flower or visits another blossom. By contrast, wind-pollinated flowers produce tiny grains of pollen that float on the breeze, with only a fraction of them happening to end up on any pistils.

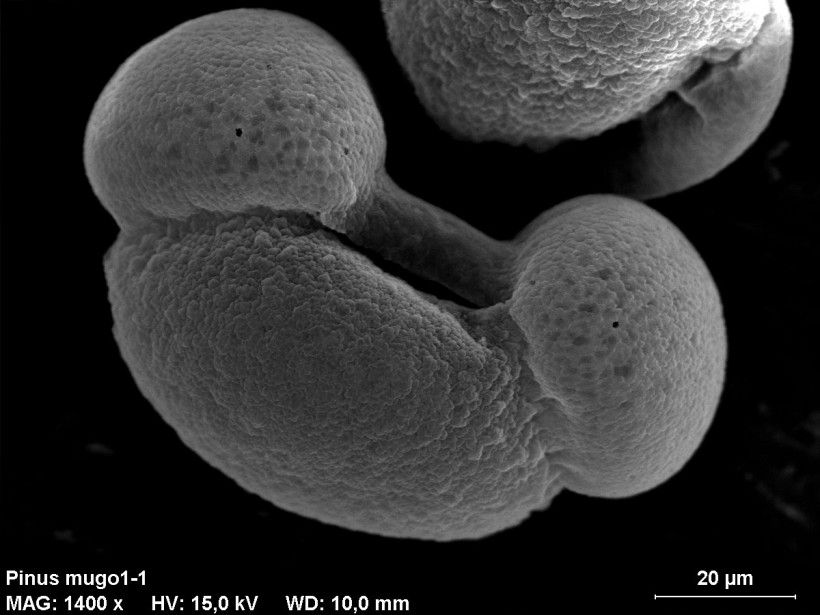

Because the odds of successful wind pollination are long, the plant produces an enormous amount of pollen. The grains are lightweight—designed to float, not stick. Some pollen has air sacs that boost its buoyancy.

Oaks and maples, some of our region’s most common trees, produce clouds of wind-borne pollen in early spring. They’re followed in mid-spring by birches, hickories, walnuts and white pines. By summer, many grasses are using the wind to pollinate (including cereal crops like wheat and corn), as are wildflowers and field “weeds.” One of the most notorious of these last is ragweed, the cause of much misery that is incorrectly attributed to goldenrods—which in fact are insect-pollinated flowers.

The ragweed/goldenrod misconception is a good illustration of the difference between flowers. Ragweed often grows in the same fields as the goldenrod—and both flower in late summer—but ragweed’s tiny, greenish flowers are easily overlooked, compared with the showy yellow plumes of fragrant goldenrod that attract hordes of bees. The images below compare two common species of ragweed and goldenrod.

Although wind pollination seems to be less complex than animal pollination, there are at least 65 species of wind-pollinated plants that evolved from insect-pollinated species. Researchers hypothesize that these changes in the past occurred in response to unreliability or scarcity of animal pollinators. As insect populations are plummeting globally due to climate change, pesticides and habitat loss, will more plants that now rely on insect pollinators evolve to rely on wind? Social distancing can be an adaptive response to environmental change, not only for humans, but also for plants.

Header Image:

Wind-dispersed pollen from a pine tree. Image by Beatriz Moisset, via Wikimedia Commons.