Beech Leaf Disease is Coming Your Way

Beech Leaf Disease—caused by an emergent species of microscopic nematode—is wreaking havoc on beech (Fagus spp.) trees, which are ecologically and aesthetically important trees across the eastern US and Canada. In the blog below, Brandywine’s Penguin Court Program Manager, Melissa Reckner, shares her firsthand experience, including how to spot the signs and the importance of raising awareness for this disease with no known cure.

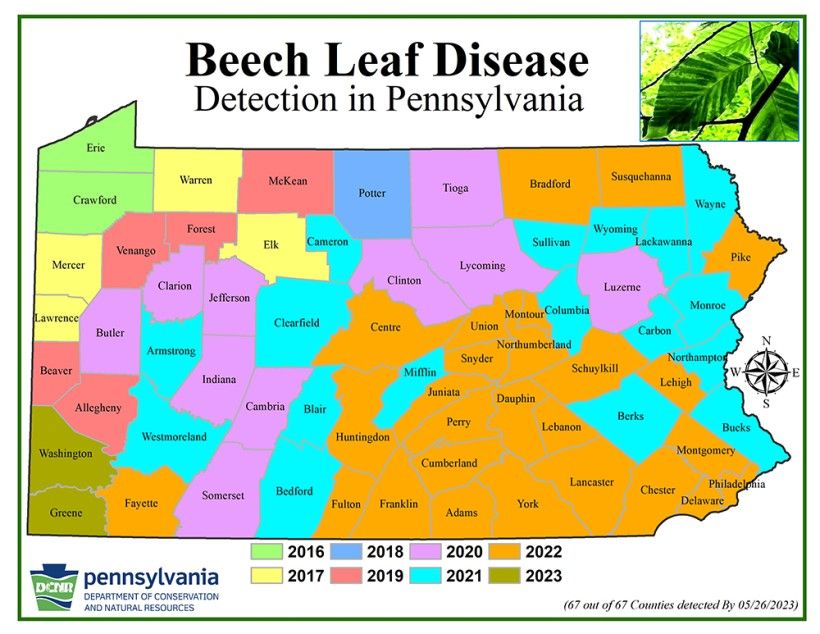

In the United States, “Beech Leaf Disease” (BLD) was first detected in Ohio in 2012 and is now in 15 states and Canada. As of 2023, BLD has been documented in every Pennsylvania county, although it is currently more prevalent and advanced in northwestern Pennsylvania. I noticed it at my house close to the Cambria/Somerset County line in Pennsylvania in 2020 and sought confirmation from DCNR in 2021.

BLD is caused by a microscopic nematode identified as Litylenchus crenatae ssp. mcannii (LCM) that invades the buds and the leaves of beech trees. The origins of LCM are unclear; however, this subspecies is similar to Litylenchus crenatae found in Japan. You can read about the distinguishing characteristics of Litylenchus crenatae in this research paper.

How it spreads

In a presentation hosted by Penn State Extension in January 2024, Mihail Kantor, Ph.D., an assistant research professor at the Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences, and his assistant, Mankanwal Goraya, explained that wind and rain can spread LCM, as can insects. Dr. Kantor reported that research has found living LCM in the frass (droppings) of caterpillars that fed on beech leaves; however, living LCM has not been documented in bird poop, so it seems birds do not directly spread it—at this time. The aforementioned research paper notes that birds “might carry mites, ticks or insects that carry nematodes.” LCM does not seem to be in the wood of beech trees, but transportation of material is strongly discouraged since LCM can live in beech leaves that might be inadvertently moved or tracked by your shoes. Be careful where you compost your leaves, too!

Dr. Kantor and Ms. Goraya shared that their research has shown that, independently, higher temperatures, higher humidity, higher wind speeds, and light precipitation (<0.25 inches) leads to higher LCM populations, but Ms. Goraya noted that when these factors were combined, as they are in nature, dispersal could either increase or decrease. For example, higher humidity and wind speed together resulted in the transmission of more nematodes, whereas higher precipitation and wind speed transmitted less.

LCM lives in beech leaf buds over winter and feeds on the developing leaf tissue. Healthy beech leaf buds are long, slender, and pointy, while infected buds become shorter and thicker as LCM populations grow. An infected bud can have thousands of nematodes and eggs. In the summer, LCM will feed on the leaves and reproduce, and in the fall, LCM will migrate back to the buds. Cold temperatures might kill some nematodes, but not all.

Spot the signs

Look for signs of BLD this spring and summer. The telltale sign of BLD is dark banding between the veins of beech leaves, which is especially noticeable when looking up into the tree so that the leaves are backlit by the sun. Infected beech leaves will also be misshapen with curling or crinkling, and they will become thicker and leathery. Some leaves may show signs of chlorosis—a condition where a leaf does not produce sufficient chlorophyll and appears yellow or bleached. As the disease progresses, leaves will become smaller in subsequent years, and it will seem like autumn in the summer as infected leaves brown and fall from the tree, resulting in thinned crowns and branch dieback. Eventually, BLD will cause beech trees to abort their buds, leading to the death of the tree. Young beech tree saplings die within 2–5 years of infection, while mature trees live a bit longer. Death from BLD is likely accelerated in beech trees stressed by drought or Beech Bark Disease, which is a different infection that involves scale insects and fungi.

Exploring treatment options and raising awareness

I was shocked and saddened by how quickly the mature, American beech (Fagus grandifolia) trees at my house succumbed. Few leaves emerged from the trees in 2023, and I consulted DCNR and a tree service company. Unfortunately, not much is known about BLD yet and, at this time, there is no known cure. The tree service company recommended a phosphite-based chemical treatment as a soil injection twice a year to bolster the tree’s defenses. The cost was $10 per inch DBH (Diameter at Breast Height) per treatment and recommended for at least five years. With over 70 total inches, the advanced progression of BLD in my trees, the uncertainty of successful treatment, and evidence of Beech Bark Disease, I made the hard decision to have my beech trees cut down.

People are trying foliar sprays or soil injections of various commercial products to stem the spread of BLD, but none kill all the nematodes, and the widespread nature of the disease makes control near impossible.

I wish I had better news to share, but an informed community is a first step, and I wanted you to be aware of the problem so you can keep tabs on your trees and potential solutions. BLD is going to dramatically change the composition of our beech forests.

Resources

Carta LK, Handoo ZA, Li S, et al. Beech leaf disease symptoms caused by newly recognized nematode subspecies Litylenchus crenatae mccannii (Anguinata) described from Fagus grandifolia in North America. For Path. 2020;50:e12580. http://doi.org/10.1111/efp.12580.

Header Image Credit: Melissa Reckner