10 Trees to Plant in a Changing Climate

As greenhouse gas emissions increase global temperatures at even quicker rates, various tree species are expected to shift farther north in search of appropriate habitats. Pennsylvania is projected to see average temperatures rise 5.2 °F by 2050 with increased precipitation and more severe precipitation events over that same timeframe. These changes could dramatically alter the species composition of our landscape.

Trees are usually thought of as stationary beings, rooted to the ground for their entire existence. While it’s true mature trees rarely move, they are actually quite mobile in their early lives. Seeds are designed to move great distances, carried by wind, water, animals, or humans. These morphological adaptations allow trees to migrate and expand their range in response to changes in local ecosystems. Today, the ability of trees to migrate is being pushed to the limit as they struggle to keep up with the accelerated changes brought on by anthropological climate change.

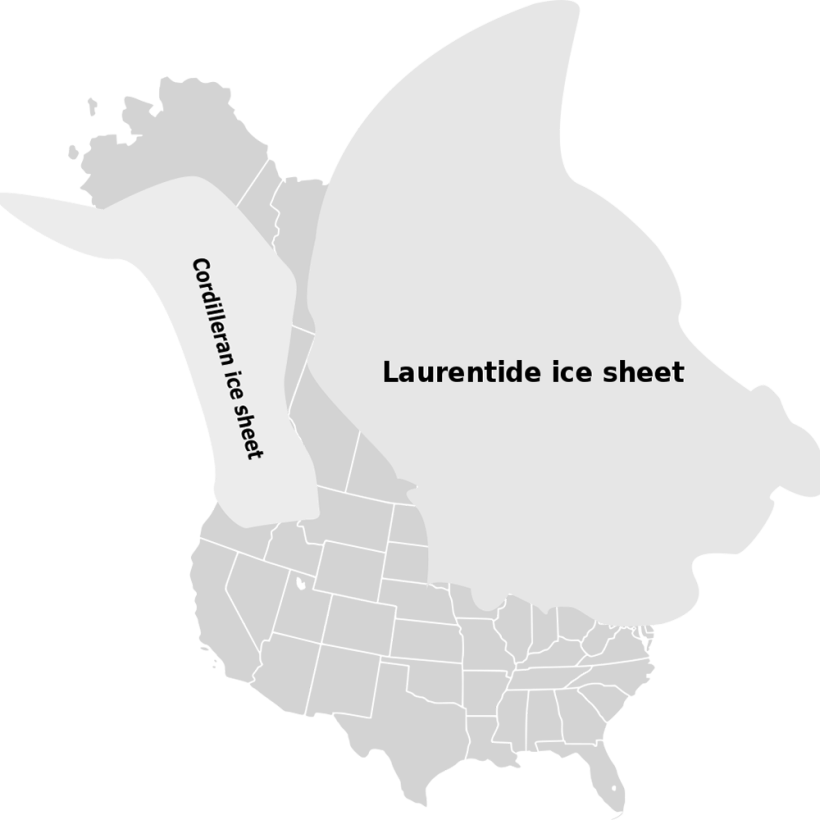

Pollen records have revealed that the distribution of trees in North America ebbs and flows with the movement of ancient glaciers. As glaciers extended southward during the last ice age, trees native to the east coast of North America were forced to migrate to relatively mild climates around the Gulf of Mexico. Since the end of the last ice age, about 11,000 years ago, trees have been migrating northward from their refuge to recolonize the forests in the northeastern part of our continent.

As temperatures rise, many cold-climate species found in Pennsylvania like Sugar Maple and Eastern Hemlock won’t be able to tolerate hotter temperatures while more southern species will expand their range north to fill the vacant niches. On top of the rapid warming, other man-made issues like habitat loss, invasive species, and migration fences further imperil the future success of many of our native trees.

Fortunately, we can make decisions today to keep the diversity of our forests intact while assisting species as they migrate towards cooler climates. Whether you want to plant street trees, add some wildlife value to your backyard, or reforest an abandoned field, selecting native trees that are suitable for an impending climate is imperative. Planting a diverse array of climate-appropriate trees will go a long way in creating climate resilient green spaces for both humans and wildlife.

Read on for a list of 10 trees that are not only projected to do well in southeastern PA and northern Delaware, but will also provide wildlife habitat, shade, and flood mitigation if used correctly. Some of these species are already common in this region and are resilient enough to survive in a warmer, wetter climate. Other species on the list currently occur just south of our region but will likely migrate north with warming temperatures. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list but instead be a starting place for things to consider when selecting trees. All the trees on this list are usually available in the native plant nursery trade.

1. Fringe Tree (Chionanthus virginicus)

A small tree with attractive blooms. Not very common in Pennsylvania as this is the northern border of its range, but it’s gaining more popularity for its ornamental and wildlife value.

2. Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum)

The northernmost limit of this species’ current range is in southern Delaware, but it’s been used for landscaping purposes much farther north. Undervalued as a street tree, bald cypress is very resilient to high winds and flooding. The small leaves and cones are noted for being easy to clean from parks and streets.

3. Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Another very resilient tree, the Hackberry does well in natural and urban settings. Its southern cousin (Celtis laevigata) prefers warmer and wetter climates so it may be more suitable for our area in the future. Both species provide food for birds and host the hackberry emperor butterfly.

4. American Elm (Ulmus americana)

The American Elm was a very common tree in wild areas and suburban streets all along the east coast until it was hit by Dutch Elm Disease. It’s making a comeback as disease resistant cultivars and hybrids are becoming more available in nurseries. Due to its high wildlife, Brandywine Conservancy preserve staff have planted clones of local disease-resistant American Elms at our preserves in an effort reestablish this species.

5. Swamp Chestnut Oak (Quercus michauxii)

There are only two known populations of swamp chestnut oak in Pennsylvania―one in Chester County and another in Bucks County. They are much more abundant in southern states and could become more common in Pennsylvania with migration assistance.

6. Willow Oak (Quercus phellos)

Another oak with a current distribution just south of our area. This is an adaptable oak that could replace some of our more cold-climate oaks like the pin oak and swamp white oak. This is important because oak trees support more butterflies and moths than any other genus in North America.

7. Yellowwood (Cladrastis kentukea)

Medium sized tree with very showy flowers. Its current range is a series of patches scattered throughout the Southeast and Midwest. It does well farther north where it is gaining more recognition as a street tree. Genetic analysis has suggested that this species was more widespread in North America but hasn’t had much success redistributing after the last ice age.

8. Sweet Gum (Liquidambar styraciflua)

Tolerant of warmer temperatures and wet areas. This tree is noted for high wildlife value and has low forage priority for deer.

9. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

The pawpaw is famous for producing the largest edible fruit native to North America. Southern Pennsylvania is at the northernmost extent of its native range but there are wild patches in Michigan and Ontario. Historians have theorized that indigenous people brought the trees north to cultivate the fruit. It’s likely this tree would be more widespread today if there were more large herbivores capable of eating and transporting the seeds.

10. Black Willow (Salix nigra)

Its current range extends from Maine to Florida. It’s a preferred species for streambank restorations and making live stakes. Willow trees host a particularly high number of caterpillars.

References:

- The Contemplative Mammoth: "How fast can trees migrate?"

- PennState Extension: "Selecting community trees in a changing climate"

- PA DCNR: "Selecting trees for Pennsylvania's changing climate"

- JSTOR: "Why Trees Migrate so Fast: Confronting Theory with Dispersal Biology and the Paleorecord"

- Shelterwood Forest Farm: "Standards for Selecting Climate Resilient Trees in the Northeast"

- Society for Conservation Biology: "Impact of Native Plants on Bird and Butterfly Biodiversity in Suburban Landscapes"

- PNHP: "Swamp Chestnut Oak (Quercus michauxii)"

Header image: Bald Cypress trees. Image credit: cappellacci, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons